Thus Terence’s “your bean will be threshed on me” ( istaec in me cudetur faba, Eunuchus 381) becomes “you’ll do the crime, but I’ll do the time” (290 and n.

13).Ĭhristenson’s translations are close to the Latin, and avoid overusing modern slang, although proverbial idioms are usually updated. In both notes and introduction, Christenson’s style of commentary is rarely dull and frequently outright funny, as when he describes the relationship between Menaechmus of Epidamnus and his wife as “terminally acrimonious” (p. The notes are thorough throughout and only occasionally redundant, though such repetitions in fact mostly seem designed to afford the same background information for students assigned to read only one or another of the plays in the volume.

#Plautus menaechmi online series

Instead of endnotes or a back-of-the-book commentary keyed to line number, we get footnotes, a decision that is well executed: for instance, in Adelphoe, a series of footnotes calls attention to characters’ recurrent concern with liberalitas, a concept that Christenson both explains and renders as English “decency” (221 n.

#Plautus menaechmi online full

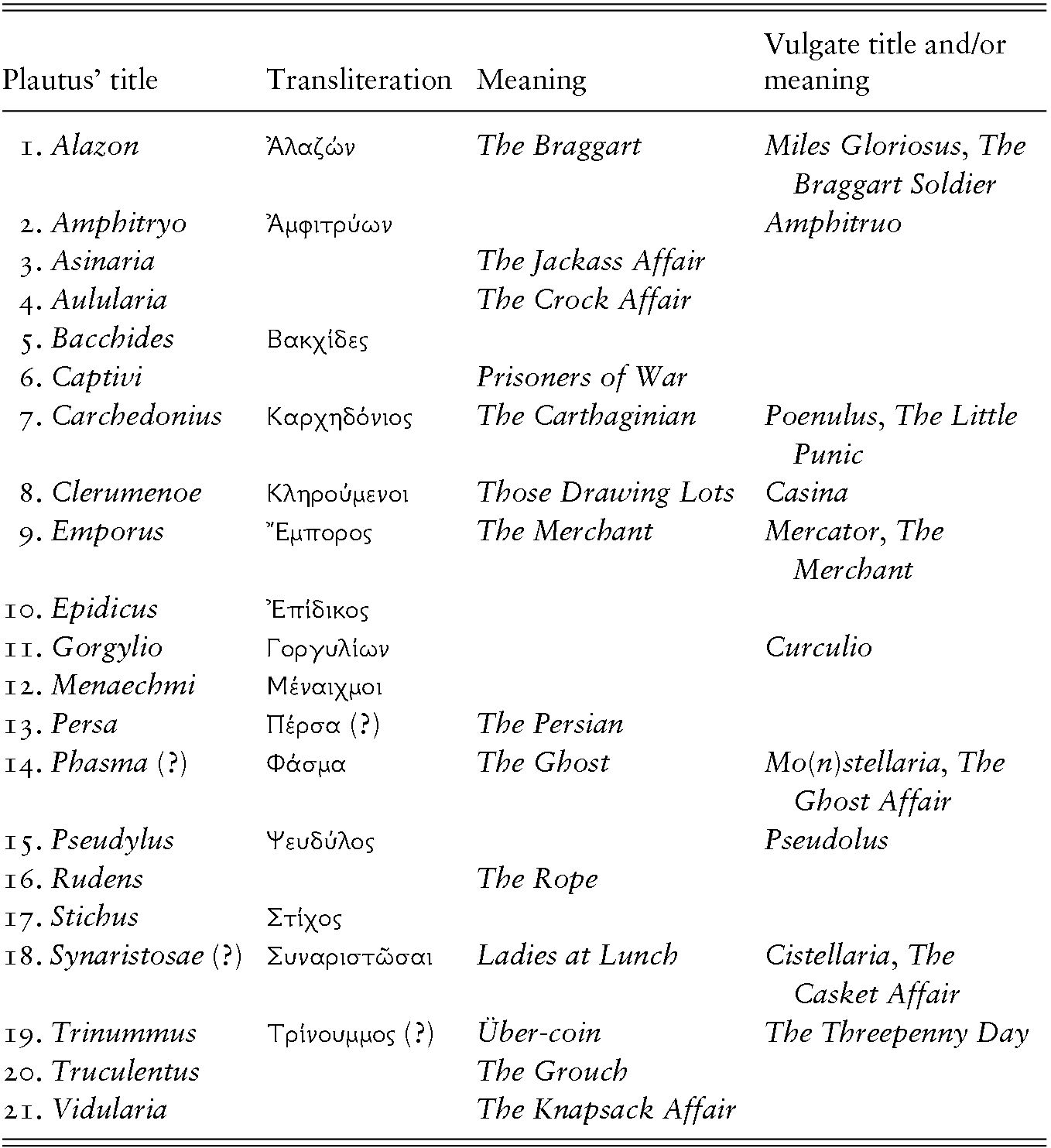

Lacunae of a full line or longer are indicated, but missing or corrupt words generally are not. (This formatting choice reveals to even the casual reader how starkly different Plautus and Terence are in their use of mixed-meter song!) Christenson renumbers each play’s scenes, but the numbering corresponds to the Renaissance act/scene breaks, as catalogued in a concordance of scenes and line numbers in the third appendix.

The cantica are italicized and indented “to mostly follow how they appear in modern Latin editions” (36) iambic and non-iambic meters both go unitalicized. The plays themselves are translated and printed in prose, with one line of English for one of Latin. Similarly, more emphasis on the importance of recognition/ anagnorisis scenes would enrich readers’ appreciation of the reunion scenes in Menaechmi, Rudens, and Eunuchus. There is, however, no systematic overview of stock types and plots after reading the introduction, one might know what an uxor dotata is, but would not know that the dowered wife is a stereotypical character in Roman comedy. 1 The first two appendices, each one page long, provide quick guides to the Olympian gods and the types of currency mentioned in the plays. This list is full without being overwhelming, and includes many of the most important publications, although no reference to work on music in Roman comedy is provided. The introduction concludes with suggestions for further reading, all in English and up-to-date. Introductions to each play draw out ideas of the “rebirth” of certain characters in Menaechmi and Rudens, the fiscal satire of the young lovers in Truculentus, the parenting philosophies and father-son relationships in Adelphoe, and the self-interestedness of all characters in Eunuchus. Separate sections on Plautus and Terence serve well as general primers on each author, and touch the surface of most of the essential aspects of their oeuvres. A section on “The World(s) of Plautus and Terence” provides historical context with helpful connections to the contents of the plays, as for example the link that Christenson makes between the comic miles gloriosus and triumphant generals during a period of Roman expansion and conquest. The introduction touches on many of the important basics of the genre: the Greek-ness/Roman-ness of Roman comedy, the transition from Old Comedy to New, the extant plays of Menander, stock types and plots, native Italian comic traditions, the religious performance context, the economics and stagecraft of the Roman theater, metatheater, contaminatio, and the polemical prologues of Terence. The introduction and notes provide ample cultural background and satisfactory discussion of the major themes of each play on a level at once accessible to undergraduates (or even high school students) and useful for scholars teaching or working on the genre.

Writing for “students and teachers in literature in translation courses, as well as the general reader,” (37), David Christenson has produced readable, entertaining prose translations that reliably reflect the content and style of these five important Roman comedies. This volume, the author’s second contribution to the Focus Classical Library (for the first, which treated four Plautine plays, see BMCR 2009.07.03), translates Plautus’ Menaechmi, Rudens, and Truculentus, as well as Terence’s Adelphoe and Eunuchus, with a general introduction and running commentary.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)